How to Make Quebec’s Forestry Sector More Competitive

Economic Note showing that the tendency to centralize forest management and reduce timeframes for harvesting should be reversed

Quebec’s forestry sector has been quietly losing steam for several years. The new forest regime has raised operating costs and reduced the accessibility of the resource, all while making supply more uncertain for companies in the sector. At a time when the forestry industry is facing new challenges, how could the regime that governs its activities be adapted to help it address them?

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Comment rendre le secteur forestier québécois plus compétitif? (Le Soleil, November 30, 2019) |

This Economic Note was prepared by Luc Vallée, Chief Operating Officer & Chief Economist at the MEI. The MEI’s Environment Series aims to explore the economic aspects of policies designed to protect the natural world in order to encourage the most cost-effective responses to our environmental challenges.

Quebec’s forestry sector has been quietly losing steam for several years. Its competitiveness has been sorely tested since the introduction of the new forest regime in 2013(1) and the end of the Softwood Lumber Agreement with the United States in 2015.(2) While Quebec has little control over trade disputes, it is solely responsible for its forestry policy.

The new regime has raised operating costs and reduced the accessibility of the resource, all while making supply more uncertain for companies in the sector. This has negatively impacted their investment,(3) and restricted their productivity gains and their capacity to develop new products and markets. At a time when the forestry industry is facing new challenges, how could the regime that governs its activities be adapted to help it address them?

Besides the softwood lumber dispute and a poorly designed forest regime, other difficulties have recently arisen. There is the expansion of protected areas, which has reduced the annual allowable cut;(4) climate change, which makes forests more vulnerable to fire, insects, and disease;(5) and the reduced demand in certain market segments (like newsprint).(6)

These new problems were obscured by a record upturn in timber prices in 2017 and the first half of 2018 due to a variety of favourable factors, notably a substantial drop in the value of the Canadian dollar, robust housing starts in Canada and the United States,(7) as well as low interest rates.

Major forest fires in British Columbia starting in the summer of 2017(8) also contributed to the price increases by temporarily reducing the supply of softwood lumber on the market. Since then, substantial inventories have accumulated,(9) and prices have undergone a serious correction (see Figure 1), while trade relations have also started to deteriorate around the world.

In spite of everything, long-term global demand for forest products, especially from emerging countries, will likely remain vigorous, and Quebec’s forests have the resources to meet that demand. For example, the use of softwood lumber has been experiencing a renaissance in residential and commercial construction since the reform of building codes, which now allow taller wooden structures to be erected, even replacing steel.(10) In sum, new innovative forestry products(11) and new markets are being developed. So why are Quebec companies slow to take advantage of this as fully as they could?

Hazards of the Current Regime

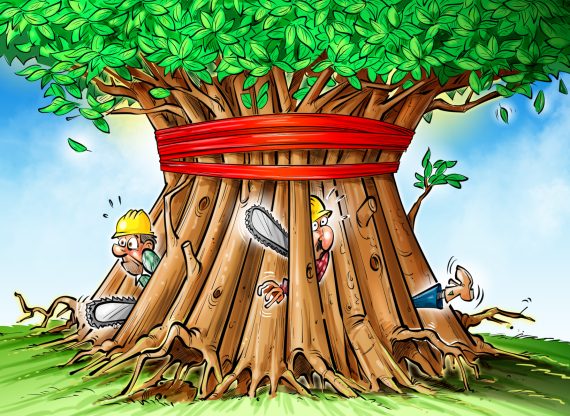

The forest regime put in place in 2013 made long-term planning more difficult for companies in the sector, and raised their supply costs.

For example, wood volumes in public forests, which were assigned without time limit under the forest concession regime, and for a period of 25 years under the timber supply and forest management agreement (TSFMA) regime, are now assigned for a period of five years or less, at the Minister’s discretion.(12) Since 2013, the volumes of wood allocated for cutting have also been reduced, and are assigned less predictably.(13) Holders of supply guarantees must therefore plan their activities on very short time horizons, which also discourages both investment and recruiting, since such decisions become riskier.

The government also took over practically all responsibility for forest management, a centralization that was presented as an improvement, since it was supposed to allow for economies of scale by increasing effectiveness in the overall management of Quebec forests.(14)

Predictably, that is not what has happened. The addition of new administrative structures instead made the planning of forestry companies’ activities more complex, and contributed to a substantial increase in their supply costs.(15) Fees paid in Quebec more than doubled between 2010 and 2014, while they should have been lowered to compensate for increased operating costs.(16)

During the same period, the auction system of the Timber Marketing Board reduced the availability of the resource for the industry, thereby creating an artificial scarcity that further raised supply costs.(17) For example, the Department reserves the right not to allocate wood if it considers that the price offered is below a limit price,(18) which creates uncertainty regarding supply and inflates costs.

Moreover, the mechanism for allocating logging rights established by Quebec was supposed to demonstrate that timber from Quebec’s public forests was not arbitrarily subsidized by government. Even though trade disagreements had always been resolved in Canada’s favour during previous disputes, it was believed that a new auction mechanism would better protect Quebec companies from American grievances. The reality was completely different: The United States reacted to Quebec’s new rules by imposing new countervailing duties, and so the dispute continues. It’s true that there was a temporary truce, the Softwood Lumber Agreement, but it ended in 2015, although the new countervailing duties were only imposed in 2017.(19)

Finally, the fact that logging rights can be awarded to a different company after another one has invested on the land, that concessions being harvested can be revoked arbitrarily, and that land already allocated can be clawed back (to expand protected areas, for example) have made access to the resource even more uncertain.(20)

The Fundamental Error

The new forest regime’s fundamental error was believing that government employees’ incentives are the same as for private companies and that the weight of the new administrative structure would have no effect on the flexibility and effectiveness of tasks carried out on the land. A report published following the implementation of the current forest regime noted among other things that the government had not adequately accounted for infrastructure costs, that the size, location, and seasonal distribution of sites had been poorly planned, and that the data used did not always correspond to the reality on the ground.(21)

In the end, costs and uncertainty increased, the availability of the resource fell, and the competitiveness of companies deteriorated, since under current conditions, they do not have an incentive to invest. If the current regime is not reformed, circumstances could lead to a costly and opportunistic government intervention aiming to save jobs in the short term, without addressing the causes of the problem.

The forestry industry urgently needs to be allowed to do what it has to in order to face the shifting challenges of global competition, while the industry’s centre of gravity is gradually transitioning to emerging countries.(22) The government should therefore modify its regulatory framework so that it no longer dissuades companies from making long-term investments in their productivity and the development of new products and markets, and at the same time seizing new business opportunities.

In contrast, delaying reform will only increase the probability that Quebec’s forestry industry will be the victim—rather than the beneficiary—of global change. Indeed, forestry operations located in Quebec are particularly vulnerable financially.(23)

The Myth of Responsible Government

It is a common viewpoint in Quebec that only the government can sustainably manage the forest, while companies think of nothing but short-term profits(24) and overharvest the resource. Yet both foreign and local experience show that this is not the case. In Quebec, it is the government that was primarily responsible for overharvesting in the past, since it overestimated the forest potential for a number of years, as the Coulombe Commission confirmed in 2004.(25)

The American example is illuminating. In the late 1980s in the United States, where a majority of forests are private property,(26) federal public forests were the only ones where more trees were cut down than planted. The owners of private forests took care to cut down fewer trees than they were able to cultivate, having an interest in preserving the resource if they wanted to be able to keep harvesting it.(27)

This should surprise no one in Quebec. The Duchesneau report, presented in preparation of the Coulombe Commission, pointed out that concession holders, who were responsible for keeping inventories and developing forest management plans, generally fulfilled their responsibilities adequately.(28)

In Sweden also, the vast majority of forests are private property.(29) Forest management planning is handled by operators, while government bodies are limited to supervising work to avoid additional costs and ensure that standards are respected.(30) In 2017, this small country was third in the world in terms of the value of its softwood lumber exports, behind only Canada and Russia.(31)

In Quebec, where the government manages practically all the forests, we harvest on average, for all tree species combined, not quite two-thirds (64%) of what the forest could provide annually while still preserving the resource,(32) which makes no sense either economically or environmentally (see Figure 2).

For the Optimal Management of the Forest

The government’s tendency to centralize forest management and reduce timeframes for forest harvesting since the 1970s should be reversed. Companies should instead be given greater latitude in developing forest management plans, as well as the ability to plan their operations over longer periods.

A decentralization of forest management will have to be accompanied by a reform of the Timber Marketing Board’s auction mechanism so that its results reflect market prices. This will reduce the costs of the forest resource, increase its accessibility, and make timber supply more predictable.

Greater autonomy for forestry companies will encourage better forest management, leading to a reduction of supply costs and of operating risks. It will increase operators’ incentives to invest, innovate, preserve, and replant in order to maximize the future value the forest can provide them, in addition to sustainably preserving the expertise that companies have built up. Finally, it will ensure companies better access to the resource and a steadier supply of timber, and also be environmentally beneficial.

More efficient forest management will not only benefit forestry companies, their employees, and the communities in which they operate. According to the Chief Forester, an optimal management of the forest will help fight climate change and protect biodiversity. This can be done by harvesting trees before they die of old age or succumb to fire, insects, or disease, releasing the carbon and methane sequestered over the years, or by replacing sick trees with more resistant species that provide a better future return.(33)

In sum, forests that are denser, made up of younger trees that grow for more of the year, and located closer to harvesting locations will permit Quebec’s allowable cut to be increased while capturing more carbon and expanding protected areas.(34) A more efficient management of the forest thus represents an economic gain for Quebec and an opportunity to reduce greenhouse gases at very low or even negative cost. Given that such solutions seem very straightforward, it is worth asking why we are struggling so much to implement them.

References

- As a result of the Sustainable Forest Development Act, R.S.Q., Chapter A-18.1. Under this new regime, in which timber supply and forest management agreements (TSFMAs) were replaced by supply guarantees of five years or less, almost all responsibility related to the forest lies with the government, including forest planning, the follow-up and monitoring of forest operations, the granting of forestry rights, timber scaling, and the auctioning off of a portion of the timber harvested in public forests. See Alexandre Moreau and Jasmin Guénette, Quebec’s Forest Regimes: Lessons for a Return to Prosperity, Research Paper, MEI, October 25, 2016, Chapter 2.

- Global Affairs Canada, Background – Canada-United States Softwood Lumber Trade, Government of Canada.

- Alexandre Moreau and Jasmin Guénette, op. cit., endnote 1, Chapter 4.

- Government of Quebec, Department of the Environment and the Fight against Climate Change, “Registre des aires protégées,” 2019; Government of Quebec, Department of the Environment and the Fight against Climate Change, “Aires protégées : rétrospective depuis 1999,” 2019.

- Statistics Canada, Human Activity and the Environment 2017, Forests in Canada, March 14, 2018.

- Government of Quebec, “Collecte sélective : papier journal,” Recyc- Québec, August 2018, p. 4; François Desjardins, “Résolu réfléchit à l’avenir du papier journal,” Le Devoir, October 16, 2019.

- Statistics Canada, Table 34-10-0135-01: Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, housing starts, under construction and completions, all areas, quarterly; Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Categories, Production & Business Activity, Housing, Housing Starts.

- British Columbia Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, “Impacts of 2018 Fires on Forests and Timber Supply in British Columbia,” Office of the Chief Forester, Figure 1, p. 3.

- Statistics Canada, Table 16-10-0017-01: Lumber production, shipments, and stocks by species, monthly, 2019; Government of Canada, Job Bank, “Environmental Scan − British Columbia: Spring 2018,” Summary, 2019.

- Radio-Canada, “Le bois remplace lentement l’acier,” March 19, 2018.

- United States Department of Agriculture, Cooperative Extension, “Wood Products – Innovation in the Forest Products Industry,” 2019.

- Alexandre Moreau and Jasmin Guénette, op. cit., endnote 1, Table 2-2, p. 22.

- Ibid., Figure 2-4, pp. 21 and 38.

- Ibid., p. 39.

- Groupe DDM, Étude comparative des coûts d’approvisionnement et de transformation : Québec/Ontario, Study prepared for the Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, March 2016, Annex 1 and pp. 4-7.

- Ibid., Annex 1, p. 1.

- Alexandre Moreau and Jasmin Guénette, op. cit., endnote 1, p. 42.

- Quebec Department of Forests, Wildlife and Parks, Manuel de mise en marché des bois, Bureau de mise en marché des bois, July 6, 2019, pp. 19-20.

- This truce was won at the cost of quotas, of the establishment of the Timber Marketing Board, and of the appropriation by the Americans of a portion of the countervailing duties that had been paid during the previous dispute. The value of softwood lumber exports, subject to the Canada-US Agreement, fell from $7.1 billion in 2006 to $5.6 billion in 2015. See Alexandre Moreau, “The Economic Costs of Protectionism: The Case of Softwood Lumber,” Viewpoint, MEI, September 2016.

- Groupe DDM, Évaluation économique du nouveau régime forestier du Québec, Report presented to the Présidente du Chantier sur les améliorations à apporter à la mise en œuvre du nouveau régime forestier du Québec, December 2014, pp. 14-15.

- Alexandre Moreau and Jasmin Guénette, op. cit., endnote 1, p. 39; Groupe DDM, op. cit., endnote 20, pp. 2-15.

- Lauri Hetemäki and Elias Hurmekoski, “Forest Products Markets under Change: Review and Research Implications,” Current Forestry Reports, Vol. 2, No. 3, September 2016, p. 177.

- Even though data on the profitability of public forestry companies are not available on a geographical basis, according to our research, forestry operations in Quebec were generally not very profitable even in 2018, the industry’s most profitable year in a while. The results for 2019 show that companies in the sector are slowing down this year. André Dubuc, “Bois d’œuvre : les scieries sous pression,” La Presse+, September 3, 2019. See also Resolute Forest Products, “Resolute Reports Preliminary Second Quarter 2019 Results,” Press release, August 1st, 2019.

- Government of Quebec, Sustainable Forest Development Act, R.S.Q., Chapter A-18.1, articles 52 and 104.

- See Guy Coulombe et al., Commission d’étude sur la gestion de la forêt publique québécoise, December 2004. According to Quebec’s Chief Forester, the government’s directives aiming to increase the timber harvest contributed in part to the 22% reduction in stocks of timber for softwood species between 1970 and 2008. Bureau du forestier en chef, État de la forêt publique du Québec et de son aménagement durable : Bilan 2008- 2013, November 2015, p. 137.

- Alexandre Moreau and Jasmin Guénette, op. cit., endnote 1, p. 27.

- Pierre Desrochers, “Comment assurer le développement durable de nos forêts?” MEI, Economic Note, March 2002, p. 3.

- Michel Duchesneau, Gestion de la forêt publique et modes d’allocation de la matière ligneuse avant 1986, Report prepared for the Commission for the Study of Public Forest Management in Quebec, May 2004, p. 10.

- Carl-Anders Helander, “Forests and Forestry in Sweden,” Royal Swedish Academy of Agriculture and Forestry, August 2015, p. 6.

- Ibid., pp. 10-11.

- Natural Resources Canada, Forest Fact Book – 2018-2019, Government of Canada, 2019, p. 19.

- Alexandre Moreau, “How Innovation Benefits Forests,” Economic Note, MEI, September 18, 2018.

- Louis Pelletier, Prévisibilité, stabilité et augmentation des possibilités forestières, Bureau du forestier en chef, December 2017, pp. 24-28.

- Idem.