Bill C-26: The Risks of Micromanaging Cybersecurity

Viewpoint explaining why, in a field like cybersecurity, private companies cannot afford to have their decision-making slowed down by bureaucratic considerations

The addition of federal administrative requirements in digital security—as Bill C-26 proposes—would lengthen the time required for companies to act and respond to breaches, according to this publication by the Montreal Economic Institute.

Related Content

Related Content

|

|

|

| Cybersécurité – Quand Ottawa veut jouer au gérant d’estrade (La Presse, December 7, 2022)

When Ottawa wants to micromanage cybersecurity (Telegraph-Journal, December 7, 2022) Cybersecurity bill could penalize instead of protect: MEI (The Suburban, December 14, 2022) |

This Viewpoint was prepared by Célia Pinto Moreira, Public Policy Analyst at the MEI. The MEI’s Regulation Series aims to examine the often unintended consequences for individuals and businesses of various laws and rules, in contrast with their stated goals.

Given the growing importance of digital technologies in our daily lives, it is vital that we ensure the safety of our computer data. To this end, the Canadian government has introduced Bill C‑26,(1) including the Critical Cyber Systems Protection Act (CCSPA), which will regulate private critical cyber systems under federal oversight(2) and will stipulate severe penalties in case of non-compliance. Yet instead of protecting the cybersecurity systems of private companies, the approach adopted risks bureaucratizing and penalizing them.

An Administrative Straightjacket

If the CCSPA is adopted, a list will be drawn up of companies with cyber systems deemed critical in several key sectors such as telecommunications and banking. These companies will have 90 days to establish a cybersecurity program and submit it to the regulatory body responsible for their sector.(3)

The program will have to, at least on paper at the time of review, ascertain and manage cyber security risks, prevent critical cyber systems from being “compromised,” and detect cyber security incidents.(4) Companies will then have to have their program reviewed annually and inform the responsible body of any modifications.

The CCSPA also imposes administrative monetary penalties if any obligation is not respected. The penalties, whose purpose according to the Act, is “to promote compliance with this Act and not to punish,”(5) can go up to $15 million.(6)

Rather than leading to better cybersecurity, however, there is a real risk that the introduction of such an administrative straightjacket, accompanied with substantial monetary penalties, will instead see an aversion on the part of private companies to taking the initiative to go beyond the minimum legal requirements. Indeed, why go to the trouble of adopting new measures to protect consumers if your program is already approved, and if doing so risks complicating your life and exposing you to millions of dollars of penalties if they are not approved?

Private Companies Are Already Ensuring Cybersecurity

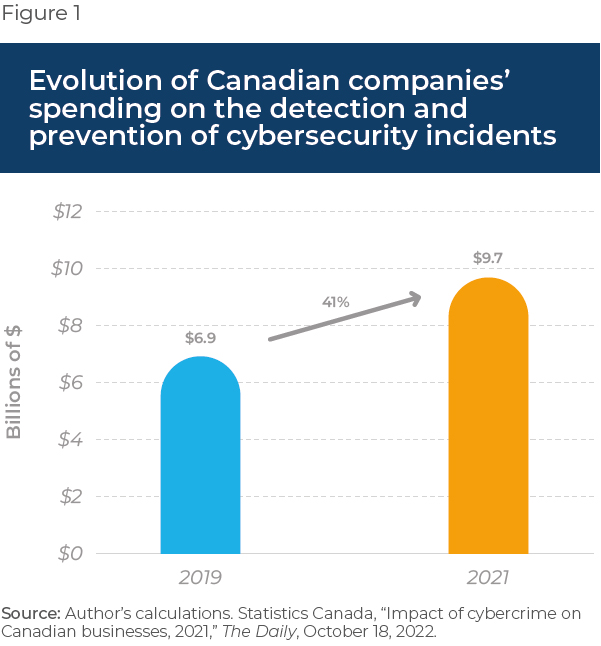

Canadian companies did not wait for Bill C-26 to start worrying about cybersecurity. They already have programs in place, and together they spent almost $10 billion in detection and prevention of cybersecurity incidents in 2021, a 41% increase—or $2.8 billion—compared to 2019(7) (see Figure 1).

In the telecommunications sector, for example, certain service providers have set up an innovative strategy that aims to strike a balance between “proactive safeguards” and “preparing for worst case scenarios” in anticipating incidents.(8) Other providers have been recognized as international leaders in cybersecurity, notably thanks to the integration of various technologies for amassing data on potential threats all while respecting customers’ wishes.(9)

The same is true of the banking sector, where 93% of CEOs consider cybersecurity as the primary motivation for investing in diverse and varied strategies.(10) These strategies include notably a collaboration among Canadian banks(11) and the hiring of “ethical hackers” to continually test institutions’ cybersecurity.(12)

While the public authorities can define the contours and the broad strokes of a cybersecurity framework, they certainly do not have the expertise that private companies have to micromanage their cybersecurity programs.

Counterproductive Micromanagement

A regulatory body that would verify every aspect of private cybersecurity programs, and that would have to approve any and all changes, would inevitably add a layer of regulatory burden to the process. This runs the risk of achieving the opposite of the desired effect, because in a field like cybersecurity, where attacks occur quickly and are constantly changing form, private companies cannot have their decision-making slowed down by bureaucratic considerations; they instead need to react rapidly, without administrative obstacles.

The Rogers outage in the summer of 2022 is a good example, illustrating how private companies respond and can themselves ensure the safety of their clients. After updating its systems, Rogers was the victim of an outage during which its service was interrupted for several hours, depriving many people of critical services like Interac(13) and access to 911.(14)

To prevent this from happening again, companies in the telecommunications sector reached a mutual assistance agreement in case of future large-scale outages.(15) The reaction would not have been as quick if regulatory bodies had impeded the responsiveness of these companies.

Cybersecurity is a real issue, and the federal government certainly has a role to play, notably in cases of state cyberterrorism. But like a referee who does not dictate to teams how to pass the puck in order to put it in the net, the government should at all costs avoid micromanaging private companies’ cybersecurity programs.

References

- Imran Ahmad et al., “Bill C-26: The increased importance of Canadian cybersecurity,” Norton Rose Fulbright, June 22, 2022.

- Bill C-26, Schedule 1.

- Imran Ahmad et al., op. cit., endnote 1.

- Bill C-26, Enactment of Act, Establishing cyber security program.

- Bill C-26, Enactment of Act, Administrative Monetary Penalties.

- Shane Morganstein, Julie M. Gauthier, and Daniel J. Michaluk, “Bill C-26: New Canadian critical infrastructure cyber security law,” Borden Ladner Gervais, June 20, 2022.

- Statistics Canada, “Impact of cybercrime on Canadian businesses, 2021,” The Daily, October 18, 2022.

- Cogeco, Putting our customers at the heart of our activities, Data security, consulted November 28, 2022.

- Bell Canada, Aligning cybersecurity with market dynamics and customer needs, October 2019, pp. 4 and 16.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Canadian Banks Collaborate to Combat Cyber Risks,” press release, March 6, 2018.

- Idem.

- The Canadian Press, “Canadian banks hire ‘ethical hackers’ to improve and test cybersecurity,” CBC News, November 22, 2018.

- Plan Hub, “2022 Rogers Outage,” PlanHub.ca, July 19, 2022.

- Radio-Canada, “Entretien avec Éric Parent : fragilité des nombreux réseaux au pays,” Tout un matin, July 12, 2022.

- The Canadian Press, “Rogers outage: Telecoms reach deal to ‘ensure’ services in emergencies,” Global News, September 7, 2022.